Uncle Vanya

The Black Box Theatre

Main Street Landing, Burlington

Saturday, Feb 28, 7.30pm

Sunday, March 1, 2.00pm

Tuesday, March 3, 7.30pm

Wednesday, March 4, 7.30pm

Thursday, March 5, 7.30pm

Friday, March 6, 7.30pm

Saturday, March 7, 2.00pm & 7.30 pm

Tickets $30 ($25 Senior / $20 Student)

“We drink because it hurts. We laugh because it hurts more”

David Mamet’s adaptation of Chekhov’s masterpiece is dark, funny, brutally honest and stained with wine and longing. Chekhov hasn’t written a tragedy, it’s a comedy with its teeth bared - the kind where people tell jokes just before their souls collapse. Yes, the play contains the existential pangs of the great Russian literature of its day, but it is much more entertaining than that… So much so, that Chekhov actually believed he had written a comedy.

A retired professor returns to his estate with his new young wife, Yelena, and in doing so stirs up old grudges and fresh desires; Vanya, his brother-in-law and custodian of the estate, drinks and jokes because he dares not consider the life he might have had; Astrov, the local doctor, makes maps of forests no one will save as he tries to ignore the brutality of the situation around him; Sonya, the professor’s daughter from a previous marriage, desperately clings to any hope she can find amid her unrequited feelings for the doctor; and all the while, Telegin, an impoverished neighbor, strums his guitar, playing the soundtrack of their lives - drunken philosophy, forgotten songs and toasts to their own undoing.

Director’s Note

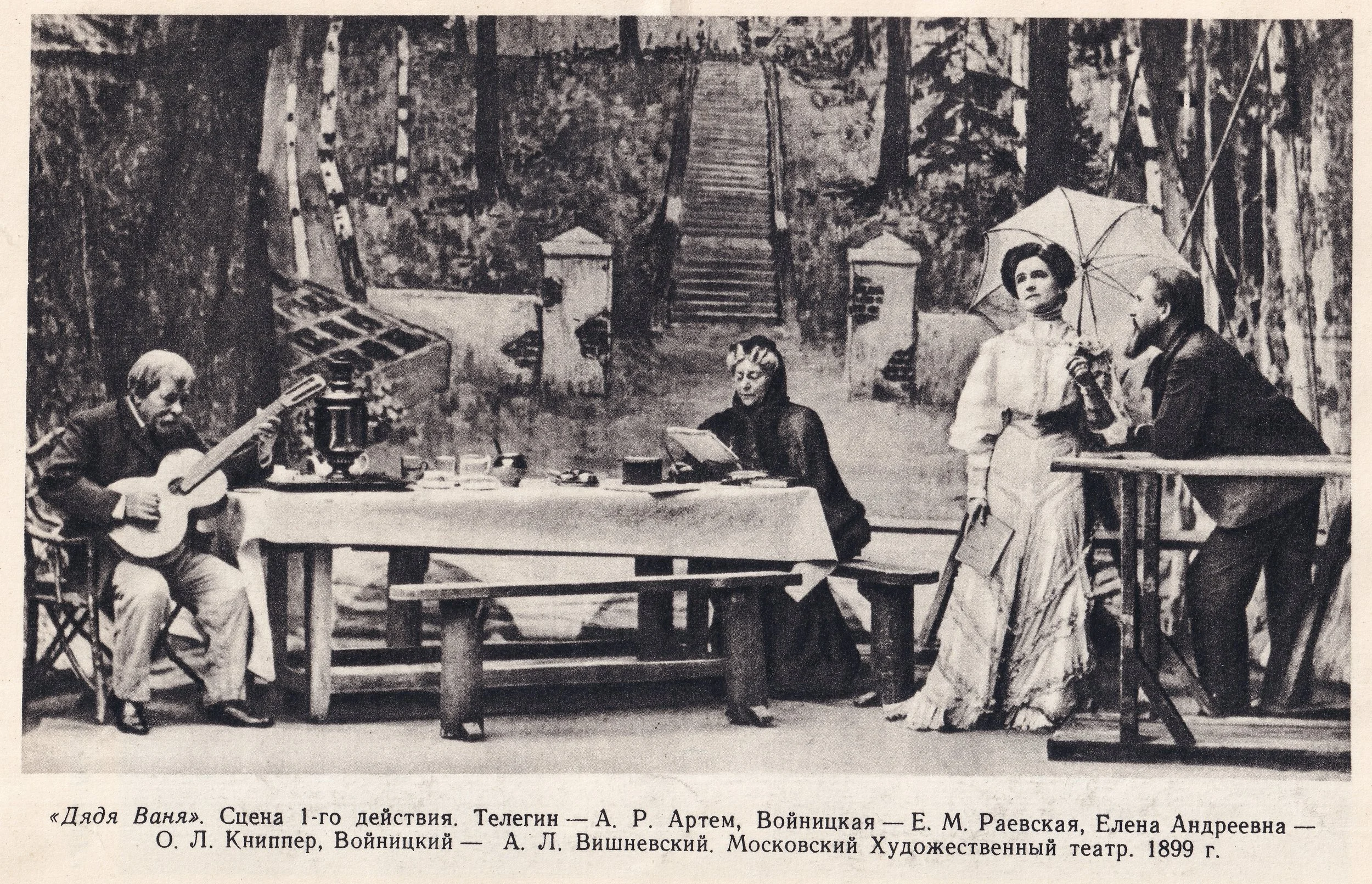

Written in 1897, and first performed in 1899, Uncle Vanya stands as one of Chekhov’s greatest works, and a cornerstone of the naturalism movement. In the late nineteenth century, advances in photography offered the sudden ability to record life as it actually was, and people became fascinated by the possibilities of detail, nuance and accuracy in art as well as life. The theatre was no exception, and the era of realism heralded Chekhov as its literary master, alongside revered stage director, Konstantin Stanislavsky, the founder of the Moscow Art Theatre, as its champion in practice.

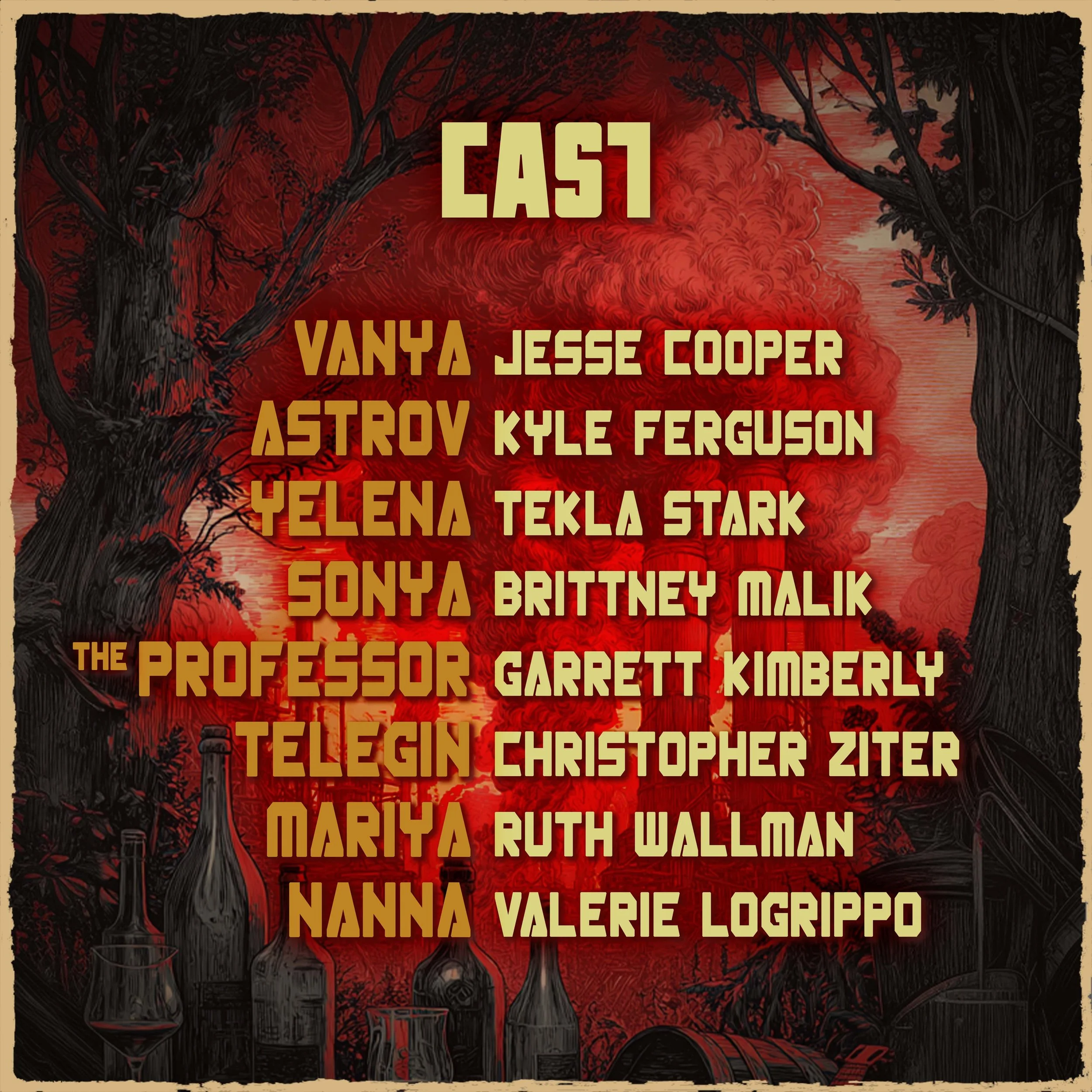

Uncle Vanya, The Moscow Art Theatre, 1899Konstantin StanislavskyDavid Mamet’s simple, unaffected style is a perfect compliment to Chekhov’s purpose, and his adaptation from a literal translation is masterful. Simply put, ordinary people do not speak in poetry, nor do they necessarily mean what they say, and in Mamet’s voice, neither do Chekhov’s characters. It is a version that allows a modern ear easy entry into the work, without attracting attention to itself or deviating whatsoever from the intention of the author, whose mighty gift was to allow the drama to exist between the lines rather than within them.

Anton ChekhovDespite going down in history as one of the great theatrical partnerships, the great director and playwright did not see eye-to-eye on many aspects of production, not least on how seriously to take the material. Still today, Chekhov’s plays are frequently performed with over-solemnity and tragic leanings that would certainly have disappointed the playwright, who maintained until his death that he was trying to depict nothing more than life as it is: its chaos, its humor, its futility, its beauty. Chekhov’s plays lack the dopamine hits of clear morality and exact explanation that are so satisfactory to the modern ear; they are beautifully imprecise in their messaging, and those who seek to extract too much literal meaning are doomed to disappointment. They are there to be watched, enjoyed and experienced simply for what they are and nothing more - much like life itself perhaps. Is that comedy, or tragedy, or does something exist which is a combination of both?

Michael Fidler, Artistic DirectorIs it still relevant?

Questioning the relevance of a hundred year old play, written in a pre-revolutionary Russia by an old white guy is reasonable, regardless of its reputation. It has a historical value, of course, as a foundation stone of modern naturalism in theatre, but beyond that, does Uncle Vanya justify its enduring popularity?

"Anton Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya” (1897) is a singularly psychologically destabilizing piece of theater that’s now being seen anew as a study of post-Covid paralysis, not to mention the existential dread of watching your life slip away by the spoonful. Although first produced in Moscow in 1899, it feels just like our present American age, when nobody hears anybody else because listening hurts too much; when the most comforting activity imaginable is a long, solitary walk followed by an even longer interlude of silence. This is a drama about being driven insane by the sound of other people’s desires, complaints and aspirations when you’re already being tortured by your own. The pandemic and the boorish political and public discourse that has followed has driven us inward, unable to fight back, going nuts like poor Vanya.

You could watch the play and mistake it for a genteel, comic trip down a quaint country road of the past and you’d be missing the entire point, which is that most of us are too civilized to survive the struggle with those to whom we’re inextricably tied.

As a trained physician familiar with pollution, disease and the destruction of the natural world, Chekhov wrote about decay and waste with white-hot, sorrow-filled rage. Yet as chilly a heart as he writes from, you can’t help but be enlivened by the ritualized thing that transpires in the dark of a theater: We’re all up there on that stage, comics dying slowly, but nonetheless still telling jokes until the show ends, not quite aware of the ways in which we’re our own sad punchlines.

Jon Robin Baitz, 2024, New York Times